Quality, not quantity: A welcome focus from the Chief Medical Officer in a report on our ageing society

Posted: 22 November 2023 | Author: Margaret Doyle | Filed under: Equalities, Mediation, Older people, research, Statistics | Tags: communities, health, mediation, Older people, research, social care | Leave a commentThere’s much of interest in this report on health and ageing by Prof Chris Whitty (Chief Medical Officer). One thing that struck me was the report’s emphasis on quality, not quantity, of life. Longevity is not his priority in this report; living a good life is. As expected, however, it’s heavily weighted towards the medical and biomedical rather than the social.

The need for robust research is highlighted, and Whitty notes that among the areas where we lack research is social care, where an evidence basis is needed to ‘help to support older people with some health problems to maintain independence and quality of life to the greatest possible extent’. I would go further and say that ‘social’ and ‘care’ are aspects of everyday life for all of us, and they are crucial to human flourishing. We need to harness the research evidence that exists on innovative ways to change how we talk about and organise care, ways that focus on flourishing and equalities. The grassroots movement #SocialCareFuture is an excellent place to start.

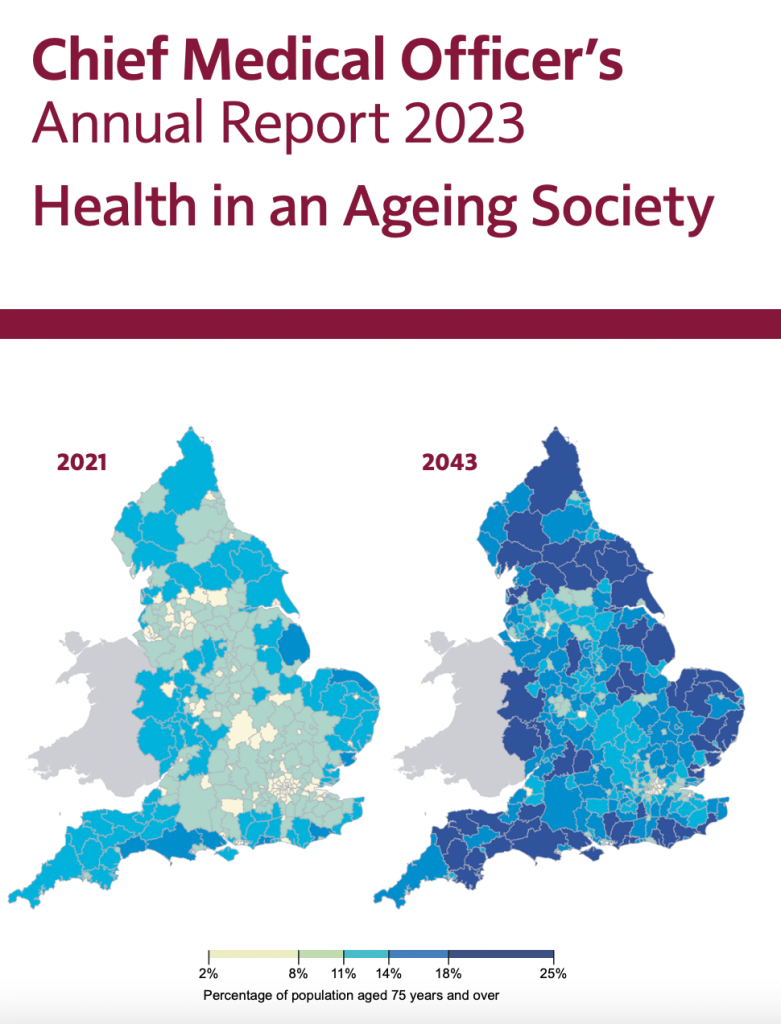

Whitty also highlights the geographical distribution of older people in England, with greater concentrations in less populated areas: ‘A large proportion of people migrate away from cities before they reach older age. The result is that metropolitan areas largely maintain their current demographic, ageing only slowly, while some areas, particularly rural, semi-rural and coastal areas in the periphery, age much faster’. Older people living in those areas are more likely to struggle with access to health care, transport and other services, and more likely to face a digital divide, highlighting the need to improve the infrastructure of support and address geographical inequalities.

We should also change the narrative about cities – they are super places for older people to live, but we often describe them as difficult, harsh, unfriendly, etc. They are not – they are full of friendly folks and a shared sense of community. Lots of opportunities to get out and about, see people, be part of the world. Green spaces too. Accessible buses. Kerb ramps. No need to have a car. Lots of free things, including free dementia-friendly workshops at museums like the V&A. Volunteering opportunities. I’m a big fan of cities as good places in which to age.

Whitty notes that ‘improving the environment for older adults includes issues around urban planning, building design, social care and aids to independent living’. We can do more, especially in terms of intergenerational fairness. Cheaper public transport is crucial, so everyone can afford to get around. Better, more affordable housing for young and old both, with a range of supported options for older people. Facilitated houseshares between young and old. Cleaner, safer streets. Reimagined social care along the lines of the vision set out by #SocialCareFuture. ‘Chat’ benches in public spaces. Community toilets. And much more.

And, of course, I would argue that all communities need access to specialist mediation services for older people, to help resolve issues that older people often face in terms of accessing services, staying in work, organising support. I’ve written here about the wide-ranging applications of such specialist mediation and its place in improving the lives of older people. There is a natural affinity between mediation and the interactions between and among people and communities and with the institutions and government bodies involved in social care and health care.

Health is an important issue for an ageing society. But it looms disproportionately large in the public imagination, something that is reflected in the current government’s priorities for legislative reform and funding. What we need is an equally large focus on the social.

Health in an Ageing Society: The Chief Medical Officer’s Annual Report 2023